The phone rings. I pick up and hear my mother on the other side. After exchange of greetings, she says she isn’t feeling good. She has a cough for the last two weeks, and has taken medicine but there’s no improvement, so she wants to get checked. The way she speaks she seems tired. She asks me when she should come (I’m a doctor and living in hostel, and being a doctor, it gives me privilege to get her checked in a hospital where I’m working and where there are long queues of patients waiting for their turn for hours just to get a minute of doctor’s precious time). I tell her to come next week because I have a busy schedule this week and I won’t be able to get her checked properly. Meanwhile she can have another course of antibiotics to see if she gets better. She agrees and hangs up, and I forget the conversation ever happened.

A week later, she calls again. She complains that there’s no improvement in her cough and it’s getting uglier. She’s coughing over the phone and I sense breathlessness in her voice. My casual attitude regarding her health changes immediately. I tell her to come over the next day. After she hangs up, my brain starts calculating and making assumptions to solve this dilemma depending upon the history she told. More than three weeks of cough . . . it could be TB, but she has no fever. She hasn’t lost weight. There are no night sweats or chills. But she’s fatigued. So more than three weeks of cough and fatigue doesn’t fulfill the criteria of having TB and if it isn’t TB, what it could be? Maybe she has just an allergy. That’s why it isn’t getting better with antibiotics, but it didn’t seem like allergy over the phone. I continue to fight with my thoughts for some time with no end result and wait for her to come.

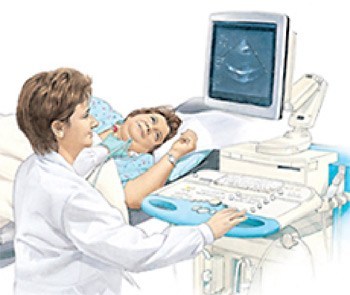

She arrives the next day. She looks tired and catching her breath with difficulty. There’s puffiness around her eyes and looks like she hasn’t slept for days. I take her to radiology department to have a chest x-ray with anticipation that her doctor will ask for an x-ray. There are no signs of TB on the x-ray film, but . . . there seems to be something far worse. The cardiac shadow on the X-ray is enlarged. A shiver runs through my spine and I begin to sweat. She looks at me and I look at her. She knows something is wrong. What is it? What’s wrong? She asks. I try to contain myself and tell her that there’s nothing wrong. Your x-ray is fine. Tell me . . . she asks again . . . tell me the truth. I repeat my answer. What should I tell her? I am not sure myself. It’s just an x-ray and I cannot make a diagnosis purely based on it. It can be nothing, but her symptoms indicate otherwise. She becomes quiet. I tell her to sit for a moment and I’ll be right back. I go out and talk to my sister over the phone (who is a doctor too) and tell her about the X-ray. She tells me to get an echocardiography (it’s a test to see how the heart is functioning).

I take her to the institute of cardiology about three miles from my hospital. All the way we are both quiet. Of course she knows something is wrong. I’m not worried or scared. In fact, I’m not feeling anything at all. I’m just numb. I’m supposed to lift her spirits up but I cannot do that. I feel wimpy myself like somebody has literally taken away my strength. We reach the hospital. I pay for the test and take her to a room crowded with patients and their families where a cardiologist is sitting in a corner behind a curtain doing echo. We sit on chairs and wait for our turn. It feels weird to be seated in a line, not as a doctor but as a family member of a patient who is my mother.

In my two years career as a doctor, I have dealt with many patients and their families. Every day when I go to hospital, I see long queues of them outside the OPD rooms waiting for their turn. One by one each of them enters the OPD room and gets themselves checked, and I as a doctor do my best in treating them. But in these two years, I have never realized what patients and their families endure while waiting outside in these long queues. Today, I am feeling that while sitting with my mother in that echo room with people, each one of them waiting desperately for their turn. The wait . . . it kills you. The longer you wait, the longer it makes you downcast and despairing and defeatist. And when you move forward in queue, it gives you a little bit of stability and hope. And the agony and stress about what is going to be the diagnosis is another war you fight with yourself while you wait.

After waiting for almost two hours, it’s our turn. The nurse calls my mother and tells her to come behind the curtain. When she’s about to go, I hold her hand and tell her not to worry. It’s just another test to make sure that everything’s fine. We don’t want to miss anything. She’s quiet and with that quietness, she just looks at me. Her gaze strikes me like an arrow and I know in that moment that when that probe of echo machine is going to be put on her chest, it’s going to change our lives forever. There’s no turning back from that. I let her go. Now she’s on the other side of the curtain. I’m counting each second on my watch. I’m terror-stricken and sweating profusely. My heart is throbbing. I can feel my bones and flesh shivering. The nurse tells me to sit, but I don’t. How can I? I’m standing beside the curtain, my ear pressed against it, trying to listen whatever the doctor is going to say. After six minutes and forty seconds, the doctor breaks the silence: for how long had you the heart problem? I hear a snap in my chest. It’s the sound of my heart breaking. I want the doctor to SHUT UP! I want to hold his tongue and tear it apart from his flesh! I want him to take his words back!

I never had heart problem, she says. Well you have, the doctor replies. She doesn’t say a word. Silence prevails again for a very long moment and I wonder in that moment about what’s happening in my mother’s head. How’s she holding on? Is she even holding on? When the doctor’s done, she comes out of the curtain. I help her out of the room and take her to cafeteria and order tea for her and tell her to stay put while I bring her report. I go back to the echo room and ask the nurse that I need to talk to the doctor. I go behind the curtain and introduce myself that I’m a doctor too and the patient he just checked is my mother and I want to know about her report. The doctor begins explaining and during the whole conversation, he tries his best to be empathetic but remains honest. We doctors know how to twist words and how to convey the worst of messages in the best way possible. According to him, she isn’t in good health.

In fact she’s quite sick. She’s in heart failure. Her ejection fraction is just 25% (it means her heart is functioning just half of the normal working heart).

25% EJECTION FRACTION!

Are you certain? I ask him. He’s certain, he says. He hands me her echo report. I stare at it like a layman. I know how to read an echo report but still I want to be assured. I’m not a doctor anymore. I’m a family of a patient who has just come to know a grim diagnosis about my mother. I ask him again, almost beg him, like asking him again will change the diagnosis, but his answer remains unchanged. In my career I had told many patients about their diagnosis and it was so easy to tell them, but what I had never realized that what it felt like to be on the receiving end, to be the one who actually has to deal with it. Well now I know! It feels like the hell has broken loose on you. You can see your whole world crumbling down in front of you. I come out of the room carrying my broken heart in one hand and her echo report in other.

25% EJECTION FRACTION!

The doctor’s words are exploding in my head. I feel nauseated and run to the bathroom and puke my guts out. Then I wash my face, look at myself in the mirror, straighten my shoulders and come out feigning to be a strong man. That’s the thing about men. They are not that expressive about their emotions. They will pretend to be strong and hide their pain until they are destroyed in their own melancholy. I go to the cafeteria. Before I enter through the door, I see her from afar. THERE SHE IS! Sitting in silence, her head tilted on her left, the wrinkles on her face so glaring that I can already see her aging through grief. I can’t see her like this. She’s crumbling inside, I can see that. Her heart is weakening every minute. This is something I never planned for – losing your mother along the way while you are building your future and in fact this future you are building is possible only because of her. NO! THIS CAN’T BE HAPPENING! NO! NO! She is the only hope I’ve been hanging on all my life and I’m not ready to lose her. Not yet. But then again you are never ready to lose your loved ones. This is a nightmare I’m having now and the irony is I’m awake. It’s not like you wake up from this and the horror events from your dream would disappear. And the most ridiculous thing about this is I’m a doctor and I can’t do anything about this. Being a doctor gives you privilege to understand certain things but in fact it’s a curse and torment as well. We, doctors, are not invincible. We do fall sick. Our families do fall sick. And the screwy part is we know already that when someone is slipping away right from your hands. We, doctors, can be on the both ends – we can heal and we can suffer. We can build and we can fall apart.

The question I wonder is: how long has my mother got? I know I shouldn’t be thinking about this and live the time with her as long as she’s living. But this question somehow finds its way to my brain. HOW LONG HAS SHE GOT? The doctors say, people with such diagnosis can live up to ten years. CAN LIVE? OR DO THEY ACTUALLY LIVE? But the doctors are not certain. They can never be certain, but you can hope to live them up to hundred years if you want. I have fought with this uncertainty for quite some time and even though it exhausts me, I’m still fighting. She’s on medication now and is better. She knows she is sick, but she still gets up in the morning, takes a load of pills and begins her day like nothing ever happened.

- How Long Has She Got? - 8 June 2020

- Labourers in White Coat - 9 May 2020

Wherever the art of Medicine is loved, there is also a love of Humanity.